Greg Nyquist |

Touring America's Northwest:

Yellowstone National Park

Editor's Note: This article is fifth in a series of travel sketches from America's northwest, including northern California, Nevada, Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, Washington, and Oregon. You can read the previous article in the series, on Grand Teton National Park, by going here.

From Grand Teton National Park, it is less than an hours drive to Yellowstone on Highway 89, following the Lewis River through a canyon recovering from the 1988 forest fires. After passing a lovely waterfall, and a fine lake (i.e., Lewis Lake), the road crosses the Continental Divide and gently leads you toward expansive Yellowstone Lake, the largest high elevation lake (7,733 feet) in the continental U.S. It's the very elevation of Yellowstone Lake, however, that constitutes its greatest flaw.What makes a mountain lake, regardless of its size, spectacular are the mountains around it: preferably steep, glacier-carved granite peaks rising well into the firmament. The mountains around Yellowstone Lake, although lofty in terms of absolute elevation (9,000 to 11,000 feet) are not very high relative to the lake. Nor are they all that close to the lake itself. Mounnt Schurz, at the eastern edge of the park, is nearly 2,500 feet higher than the lake, and would approach the spectacular — if it rose right next to the lake. But the top of Mount Schurz is seven or so miles away, and can only be appreciated from the remote southeast arm of the lake.

the road crosses the Continental Divide and gently leads you toward expansive Yellowstone Lake, the largest high elevation lake (7,733 feet) in the continental U.S. It's the very elevation of Yellowstone Lake, however, that constitutes its greatest flaw.What makes a mountain lake, regardless of its size, spectacular are the mountains around it: preferably steep, glacier-carved granite peaks rising well into the firmament. The mountains around Yellowstone Lake, although lofty in terms of absolute elevation (9,000 to 11,000 feet) are not very high relative to the lake. Nor are they all that close to the lake itself. Mounnt Schurz, at the eastern edge of the park, is nearly 2,500 feet higher than the lake, and would approach the spectacular — if it rose right next to the lake. But the top of Mount Schurz is seven or so miles away, and can only be appreciated from the remote southeast arm of the lake.

Relative elevation is, indeed, the great problem with Yellowstone, compared to other mountain-based national parks. Consider Grand Teton National Park, just to the south. The scrubby plains that make up the eastern part of the park are nothing to boast about, but it hardly matters, because the Tetons themselves rise up to 7,000 feet over those uninspiring plains — and there are few things more spectacular than a mountain suddenly springing 7,000 feet into the air. Much of Yellowstone rests on the so-called Yellowstone Plateau, a massive volcanic field that contains the largest volcanic system in North America. The Yellowstone Caldera is considered a "supervolcano" with enough bottled-up force to kill thousands of people and drastically alter global weather.

When one thinks of volcanoes, one thinks of massive mountains, like Mount Rainier or Mount Shasta, not plateaus with calderas half-covered in water. The mountains surrounding Yellowstone Plateau are only a few thousand feet higher than the plateau itself. So while Yellowstone is rarely less than beautiful, in only a few places does it attain the sort of spectacular beauty seen in other mountain-based national parks, such as Yosemite, North Cascades, and Glacier. This is true even if we discount the effects of the 1988 fire, which burned a third of the forest of the park. A high mountain plain decorated with pine or fir tress is very pleasant item to contemplate, but it doesn't attain the jaw dropping beauty of mountain valley surrounding by towering granite peaks and dotted with lakes nestled in glacial cirques.

When one thinks of volcanoes, one thinks of massive mountains, like Mount Rainier or Mount Shasta, not plateaus with calderas half-covered in water. The mountains surrounding Yellowstone Plateau are only a few thousand feet higher than the plateau itself. So while Yellowstone is rarely less than beautiful, in only a few places does it attain the sort of spectacular beauty seen in other mountain-based national parks, such as Yosemite, North Cascades, and Glacier. This is true even if we discount the effects of the 1988 fire, which burned a third of the forest of the park. A high mountain plain decorated with pine or fir tress is very pleasant item to contemplate, but it doesn't attain the jaw dropping beauty of mountain valley surrounding by towering granite peaks and dotted with lakes nestled in glacial cirques.

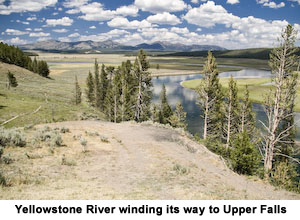

One of the places where Yellowstone does verge into the spectacular is the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. The Yellowstone River, spilling out of Yellowstone Lake, gushes through a pleasant valley full of lush grasslands dotted with buffalo. Following the river, one soon finds oneself looking into a steep, yellow- and orange-tinged rhyolite rock canyon of unsurpassable beauty. Two spectacular waterfalls grace the canyon: Upper Falls and Lower Falls. In the western United States we have any number of spectacular waterfalls. Most, however, come from relatively small streams, like Yosemite Falls or Multnomah Falls. Even the Merced River, which produces Vernal and Nevada Falls in Yosemite, does not sends as many gallons of water over a its two cliffs as does Yellowstone River through its dropp-offs. Lower Falls sends the full force of the river plunging 300 feet into the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. The roar of the falls and the mist rising from its giddy descent are a sight to behold. In the afternoon, the mists spawn colorful rainbows.

One of the places where Yellowstone does verge into the spectacular is the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. The Yellowstone River, spilling out of Yellowstone Lake, gushes through a pleasant valley full of lush grasslands dotted with buffalo. Following the river, one soon finds oneself looking into a steep, yellow- and orange-tinged rhyolite rock canyon of unsurpassable beauty. Two spectacular waterfalls grace the canyon: Upper Falls and Lower Falls. In the western United States we have any number of spectacular waterfalls. Most, however, come from relatively small streams, like Yosemite Falls or Multnomah Falls. Even the Merced River, which produces Vernal and Nevada Falls in Yosemite, does not sends as many gallons of water over a its two cliffs as does Yellowstone River through its dropp-offs. Lower Falls sends the full force of the river plunging 300 feet into the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. The roar of the falls and the mist rising from its giddy descent are a sight to behold. In the afternoon, the mists spawn colorful rainbows.

There is no accounting for taste, yet it is a fact nonetheless that more people go to Yellowstone to gape at the geysers than to gape at the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. Because of its proverbial reliability, Old Faithful is the most popular and famous geyser in a park littered with thermal anomalies. It gushes forth about every 91 minutes or so, and thousands flock to see it do its thing. There is a huge parking lot adjacent to the geyser — the largest such parking lot I have ever seen in a national park. On a Wednesday in July, it was jammed pack — hardly a spot left open in entire lot. I was fortunate enough to filch an empty space in back of one of the stores while filling up at the gas station — otherwise, I hardly think I could have found a place to park anywhere in that mad scramble of cars coming and going, going and coming. Hint to the wise: if you really must gape at a geyser, perhaps the best time to go see Old Faithful is in the wee hours of the morning, when Phoebus' rays are just beginning to illuminate the eastern horizon. In other words, get there when most people are still asleep.

There is no accounting for taste, yet it is a fact nonetheless that more people go to Yellowstone to gape at the geysers than to gape at the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. Because of its proverbial reliability, Old Faithful is the most popular and famous geyser in a park littered with thermal anomalies. It gushes forth about every 91 minutes or so, and thousands flock to see it do its thing. There is a huge parking lot adjacent to the geyser — the largest such parking lot I have ever seen in a national park. On a Wednesday in July, it was jammed pack — hardly a spot left open in entire lot. I was fortunate enough to filch an empty space in back of one of the stores while filling up at the gas station — otherwise, I hardly think I could have found a place to park anywhere in that mad scramble of cars coming and going, going and coming. Hint to the wise: if you really must gape at a geyser, perhaps the best time to go see Old Faithful is in the wee hours of the morning, when Phoebus' rays are just beginning to illuminate the eastern horizon. In other words, get there when most people are still asleep.

Increasingly, people go to Yellowstone, not to gape at geysers or bask in the roar and feel the cool mist of Lower Falls, but to see the wildlife. Bison, wolves, grizzlies, moose, elk, deer, pronghorns, bighorn sheep all make Yellowstone their residence of choice.  And while you're not like to see a grizzly or a wolf, you can't miss the bison: they infest the park like fleas infest a dog, choking the roads and block traffic. If you honk at them they just stare back at you, blinking apathetically.

And while you're not like to see a grizzly or a wolf, you can't miss the bison: they infest the park like fleas infest a dog, choking the roads and block traffic. If you honk at them they just stare back at you, blinking apathetically.

Strange to say, yet it is nevertheless true that bison are the park's most dangerous animal — dangerous, that is, in terms of injuries to human beings. More dangerous than the fierce and ill-tempered grizzly. There is a good reason for this: there are a heck of a lot more bison in Yellowstone than grizzlies, and if you wind up having an unpleasant encounter with an animal in the park, it will likely be a bison that you've gotten yourself mixed up with (or mixed up by). Although a bison will not kill you to eat you, he may trample you to death out of either carelessness or irritation. Always there are foolish people who wish to get up close and personal with these massive, lumbering but none too intelligent beasts — God only knows why. Bison are hardly all that comely or pleasant up close and personal. They have unkept,mangy hides and they stink something awful. Better for all concerned, and much preferable to the olfactory sensibilities, to enjoy from a safe distance.

One of the advantages of urban life, from a purely egalitarian point of view, is that it gives a much wider latitude to foolishness than does the great outdoors. In the city, a congenitally foolish person has a very good chance of surviving well into manhood, particularly if he has relatives with money or knows which lines to stand in at the welfare office. Things stand otherwise in the wilderness, where foolishness is promptly trampled or frozen or eaten to death, without anyone making so much as a cursory genuflection to fairness or social justice. This, in a nutshell, helps explain much of the difference between red and blue states. The blue stater is primarily an urbanite who, shielded from the rod of nature by the various state funded safety nets, knows little of the harsh realities at the core of human existence. Things stand otherwise with the typical red stater, who tends to a less urban, more rural, and thus closer to the primal realities of the universe.

One of the advantages of urban life, from a purely egalitarian point of view, is that it gives a much wider latitude to foolishness than does the great outdoors. In the city, a congenitally foolish person has a very good chance of surviving well into manhood, particularly if he has relatives with money or knows which lines to stand in at the welfare office. Things stand otherwise in the wilderness, where foolishness is promptly trampled or frozen or eaten to death, without anyone making so much as a cursory genuflection to fairness or social justice. This, in a nutshell, helps explain much of the difference between red and blue states. The blue stater is primarily an urbanite who, shielded from the rod of nature by the various state funded safety nets, knows little of the harsh realities at the core of human existence. Things stand otherwise with the typical red stater, who tends to a less urban, more rural, and thus closer to the primal realities of the universe.

The least famous part of Yellowstone is the northeastern section of the park, where few roads or trails can be found. From Canyon Village, located in the center of the park, the road to Tower Fall rises out of the caldera and gradually ascends to the park's highest pass (Dunraven Pass, 8,859 feet), then makes a quick swerve along the side of the parks highest easily climbed summit (Mount Washburn, 10,243 feet),then ascends into the rough, scraggly environs between Tower Junction and Mammoth Hot Springs. Pretty enough country, I should imagine, decked in Autumn colors or blanketed in winter snow. Hardly spectacular in any season, however: simply rugged, high hills, verging here and there into broad peaks, speckled with burned trees, scorched in the 1988 fires. Eventually, after tediously winding through this bit of the Rockies, you enter a section of the park dominated by grasslands, with occasional clumps of trees. Elevation is slightly lower here (between 6,000 and 7,000 feet) and, perhaps because it is on the wrong side of the Rockies, it seems drier. The elevation increases a bit as you drive into Mammoth Hot Springs, with its striking tavertine terraces, glistening in the morning sun.

From Mammoth Hot Springs it is a short drive to Gardiner and Yellowstone's north entrance. From here, Highway 89 lines up with Yellowstone River and follows it all the way to Livingston through what may be the drabbest approach to a mountain-based national park to be found anywhere in the U.S. Dull, dry, dirty grasslands verging on either side into steep nondescript hills, with the gushing Yellowstone, bereft of its spectacular surroundings in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, swirling headlong towards its ignominious terminus in Lake Sakakawea, just across the North Dakota border some 440 miles away.

No use following the Yellowstone any further than Livingston. If you find yourself in southern Montana, the first thing to do is to get yourself out of the section of the state and head straight to northwestern Montana, where all the best scenery is to be found.

Greg Nyquist is the webmaster for jrnyquist.com. He can be reached at machiavel@mac.com.